Closure.org Blog

By accessing www.closure.org, you have made a powerful decision to educate yourself about end-of-life issues and care options. Dying is an uncomfortable topic to consider… no matter what your age. But it’s an important matter to discuss with family members and healthcare providers. You need to know what you want, and what you want to avoid, in the event that your time becomes limited.

There is a great deal of information available about end-of-life. In fact, it can be quite overwhelming. This Web site is designed to simplify that information. We’ve developed simple, easy-to-use online educational materials, tools and resources to help you make informed end-of-life decisions that are consistent with your values and beliefs.

|

This past December, Nancy Zionts, chief program officer for JHF, posted an entry about end-of-life discussions on the Health Affairs Blog. That entry is below.

|

End-of-life care presents emotional, physical, and financial burdens for patients and their loved ones. At the Jewish Healthcare Foundation (JHF), in Pittsburgh, we have become somewhat fixated on the fact that the health care system too often fails families and patients at end of life. Unfortunately, failure is what most people expect. But JHF end-of-life initiatives in the Pittsburgh area are showing that better realities are possible.

Recently, the Dartmouth Atlas Project released its first-ever report on cancer care at end of life, which showed that one in three Medicare cancer patients spends his or her final days in hospitals and intensive care units (ICUs), an indication that many clinical teams aggressively and often futilely treat patients with curative care close to the times of their deaths. The report suggests that we are underutilizing hospice and palliative care, which receive high marks from families and patients at end of life.

Heaven forbid, if someone you loved was suffering from a stroke, you’d want them cared for somewhere where they would get the state-of-the-art care, right?

The Joint Commission (TJC) has certificate programs to recognize hospitals that meet or exceed the standards for stroke care; if your loved one is admitted to such a hospital, you get the reassurance of knowing they have TJC’s endorsement.

Now, what if your loved one was suffering from severe pain, anxiety, shortness of breath, or having a crisis of faith as a result of the treatment for one of the diseases above? Wouldn’t you also want state-of-the-art-care for those problems?

By Dr. Jonathan Weinkle

The longer I discuss end-of-life, the more stories I hear, the more nuanced my view becomes. Last month I facilitated a fascinating discussion that was meant to open an honest conversation about death and dying, to break down what I often call the Brighton Beach Memoirs approach to death – that is, whispering the word out of fear that, if we say it out loud it might happen to us.

The discussion ended with a personal story from one of the participants who was dying – her words, and her doctors – of a liver abscess two years prior, only to come back “escaped to tell thee” like one of the messengers coming to Job. What had saved her was a surgery that had one chance in a hundred of succeeding, and who knows what chance of leaving her dead on the operating table. Why was she undergoing the surgery? Her daughter insisted that, “If she’s going to die anyway, why don’t you operate? What have you got to lose?”

Sounds like anathema to the usual message of “caring before curing,” doesn’t it? Yet it is hard to argue with the outcome of this previously dying woman who walked into the room under her own power, sat attentively in a lecture and discussion for an hour, and chose this moment at the waning of our hour to articulately tell the story of how reports of her death had been greatly exaggerated.

From the John A. Hartford Foundation Blog

By Amy Berman

Shortly after I was diagnosed with inflammatory breast cancer a scan showed a hot spot on my lower spine. Was it the spread of cancer? My oncologist scheduled a bone biopsy at my hospital, Maimonides Medical Center, in order for us to find out.

A few days before the procedure, I went in for preadmissions testing. As part of my formal intake, in addition to collecting my insurance information and poking and prodding me a few times, the nurse asked me if I would like to fill out an advance directive. This was not because she was a miraculous oracle who knew the outcome of my biopsy, which would leave me with a Stage IV diagnosis. No, her question was merely standard procedure. I said yes, and shortly, a specially trained social worker arrived to walk me through the process.

A cheerful young woman reminiscent of a camp counselor sat down next to me with papers neatly attached to her clipboard. The first step, she explained, is appointing a health care proxy, someone you trust to make health decisions for you should you become incapacitated. Being a nurse, I knew this, but it was comforting having someone there with me while I filled out the form. I chose my mother. Since my diagnosis, she and I had had numerous conversations about what I wanted should my disease progress and take away my quality of life. I trusted that she would respect my wishes, even if that meant making painful decisions as my disease progresses.

By Toni Steres

My grandfather is dying. I tear up just typing that sentence. He was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in August of 2010 and without going into details, was given 6 months to a year back in December of the same year.

As a registered nurse, I know how important it is for patients to make end-of-life decisions before you actually need them. I have many stories of patients who planned ahead—and ones where patients did not. As you can imagine, those who did not left their families in turmoil—“What did he want to have happen? Do you know? Does anyone in the family know?”

I hoped that my grandfather, being a planner himself, would be willing to discuss this with me. But the denial stage of grief is a powerful thing. When I first brought up the thought that plans needed to be made—he cringed and changed the subject. Later, he told my father that it depressed him when I brought up the subject.

By Hilary Kramer

For the past five-and-a-half years, I have worked for a small hospice, in a community where everyone seems connected by some thread. Hospice work is a very rewarding field; we often get to know one patient and family, and then later provide care for other family members who are referred to us. This community seems to be getting a handle on what services are available and are utilizing that information in order to better deal with the process of death and dying. I am in awe of the way this community is connected to one another for the greater good.

Given my background, it should be easy for me to discuss the subject of death. Some families never talk about death, as if it will never happen if we don’t say the words. Others seem to talk about death as an “if.”… And still others seem to have an ongoing dialogue for years and discuss every aspect of an illness and funeral. I have found that everyone starts at a different point. There is no wrong way to start a conversation, no matter where it begins. It is my job to work from every starting point and help as if each person and family is starting from the beginning of the conversation and process of dying.

It seemed strange, then, that I found myself talking to my siblings about hospice for my father, who was 90, and dying from complications of Alzheimer’s disease. He was diagnosed only six years ago, but thinking back there were signs before then that we chose to ignore, because my mother was the one caring for him on a daily basis. My mother passed away quickly one morning, which left us to try to figure out what to do for dad, while grieving for her. I flew to Florida, as did my two brothers, and began the daunting task of trying to figure out where to begin.

By Adam Conway

During the past year I have had the opportunity to say goodbye to my father’s mother and my mother’s father. They each died peacefully in their homes with family standing by, and I felt lucky to speak to them in their last hours. From their perspectives, a long, fulfilling, and successful life was at its end. My Grandfather had served in World War II, opened and maintained a successful business, and raised a family. My Grandmother, just months shy of 100 years old, had seen more changes in the world than I can begin to understand.

Despite the fact that each of them had been aware for many years that they would likely pass on soon, they each had chosen to communicate with my generation in a way that glossed over illness and frailty, although when I asked my grandma for advice last year, she said “Don’t get this old! Then again, I don’t much care for the alternative!”

By Mike Light

We were all winded and drenched in sweat, having just completed a high-intensity workout on a particularly humid June evening. Lying on the grass, recovering, we began to discuss a common topic for us: nutrition and the best place to buy fresh produce. Our workout group is composed of six recent college graduates. We are educated, socially informed, and try to live as healthy a lifestyle as possible. But while we care deeply about our own wellbeing, in an effort to prolong our lives, we never took the time to think about the end of our lives.

Since I started working on the Closure Intiative, I have become more enlightened to end-of-life issues. Even though I volunteer as an Emergency Medical Technician and have helped patients not much older than myself who were seriously ill or injured, it never struck me that someday I could be in a terrible car wreck, or fall seriously ill. Yet, more than 30,000 Americans 15 to 24 years old die every year, over half from unintentional injury. In the age of modern medicine, many of these deaths are preceded by invasive interventions and aggressive procedures. So, lying on the grass, I asked my workout buddies if they had ever considered end-of-life care. What kind of treatment would they want if they wound up in the hospital? Would they want to be on a breathing machine? Did their families know their values and their wishes? Were these wishes in writing? They each had strong opinions about what level of aggressive care they would want to receive and how much quality of life they were willing to sacrifice for an attempted treatment. Perhaps not surprisingly, they did not have their wishes spelled out in writing, nor had they had serious discussions about the topic with their loved ones – the people who would have to make decisions on their behalf if they became incapacitated.

By Stefanie Small

The Chevra Kadisha (Ritual Burial society) has been part of my life for as far back as I can recall. My parents are longtime members of this volunteer group of people who, as part of the Jewish tradition, prepare the deceased for burial. The members wash the person and dress them in shrouds and ready them for the final leg of this life’s journey. It is considered a “chesed shel emet,” a kindness of truth, done for no other reward than the knowledge that someone will do it for them when the time comes.

I became a member of the society about 10 years ago and have never looked back. It is a life altering experience to be part of the conclusion of a person’s existence in our world. The room where the work is done is quiet, almost reverent, as we know that we are the last to wash and dress this person. We are the final people to see the whole person as we place them in their caskets. And it is peaceful and hopeful and a reminder that life is precious.

By Marian Kemp

Talking about care at the end of life is not easy. Yet communicating wishes for care in the final months is important. It helps to ensure wishes are honored and eases the burden on loved ones.

Seriously ill patients and/or their families may hear of a document that can help ensure that an individual's health care treatment wishes at the end of life are respected. This document, called the Pennsylvania Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment or POLST, was approved for use in Pennsylvania late in 2010 by the Secretary of the Department of Health (DOH).

The POLST form is recommended for persons who have advanced chronic progressive illness and/or frailty, those who might die in the next year, or anyone of advanced age with a strong desire to further define their preferences of care in their present state of health. To determine whether a POLST form should be encouraged, healthcare professionals ask themselves, "Would I be surprised if this person died in the next year?" If the answer is "No, I would not be surprised", then a POLST form is appropriate.

Read more: Pennsylvania Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST)

Michelle Anderson

After she had experienced a few stays in the intensive care unit, I spoke with Sharon, a family member, about her preferences for care at the end-of-life. If she was ill again and things did not go as we'd hoped, what would she want? If the doctors aren't able to wean her off the ventilator, what should we do? She responded by saying "You made the right decision last time."

Several years passed by and fortunately Sharon was in good health. My husband and I recently saw Sharon at Thanksgiving along with our extended family, including Aunt Jean, who was feeling slightly under the weather with a cough. Thinking that it was nothing but a cold, my husband and I gave our ritual hugs and said goodbye. As we left, we smiled when we thought of her cheerful personality and the spunky glitter hat she was wearing, which fit her to a T.

By Jonathan Weinkle, MD

Every doctor and nurse knows what the vital signs are. There are four of them: pulse, respiratory rate, temperature and blood pressure. They are called vital, meaning crucial. Meaning alive. Meaning essential – both to the patient, who cannot live without them, and to the medical system, which cannot function without them.

More recently a fifth vital sign has been added: oxygen saturation. Surely to a creature that breathes air in order to live this is crucial, too. So there are five vital signs, five numbers that we must know about everyone in order to know anything about them at all.

That is, until they are dying. When vitality is about to be extinguished, how vital are the vital signs? How necessary, how crucial, is it to awaken the old man from a peaceful sleep to discover these formerly all-important pieces of information? When all have understood that death is approaching? After all, if we find the vital signs are abnormal, that there is a fever, or elevated blood pressure, or slow breathing, what will we do? Will these bits of data tell us anything other than what we already know – that the end is near?

By Jonathan Weinkle, MD

A response to a news item about Dan Chen’s Last Moment Robot

So long as it doesn’t drown you in food that you cannot taste and your body can’t use

By Jonathan Weinkle, MD

Joe Klein has spent most of his adult life on the presidential campaign trail, reporting for Time magazine on presidential politics. He asks hard questions and provides sharp analysis of both Democratic and Republican candidates. One wonders if, in 2012, he will have a new, difficult question to ask, born of his recent personal experiences.

Klein’s parents recently died, each of them after the long series of illnesses that typifies how older Americans die in this day and age. His mother succumbed to pneumonia in the end, and his father to kidney failure. In a recently published Time cover story and accompanying video, he discusses the experience.

Nothing Klein says will be news to anyone who has recently experienced the death of an older loved one. Procedures were done, like repeated lab draws and placement of a feeding tube, that did not add length of life, but did add to the burden of suffering. The feeding tube was placed because when the doctor in Pennsylvania called Klein in Chuck Grassley’s kitchen in Iowa and said, “We have to put in a feeding tube or we’ll lose her,” he felt like he didn’t really have a choice at that time. The whole truth of how soon Mrs. Klein was likely to die didn’t come out until after the time was already in.

A long strand of pink glittery hair was flowing in the breeze. An equally fashionable purple strand highlighted the opposite side of a thinly contoured face. This wasn’t a spunky 13 year-old girl. This was my patient, Mr. T, being swiftly wheeled into the gym by his young daughter who had yet to perfect her driving skills. “Look!” she exclaimed. “I bought my dad some presents,” she said as she gestured to the clip-on hair pieces that donned Mr. T’s head. “Don’t I look beautiful?” he asked while playfully tossing his head from side-to-side.

As a graduate student finishing up the last months of my occupational therapy (OT) degree on an inpatient rehabilitation unit, Mr. T was one of my first patients whom I was completely responsible for all aspects of his therapy. He was in his mid-50’s and just had a large hematoma drained from the right side of his skull. I had no idea what to expect when I first walked into Mr. T’s room, but I quickly came to know him as a caring and humorous individual who was full of life. He was constantly surrounded by his family (with six children it’s difficult to find some alone time!) and by members of his church. Through the advances and set-backs in Mr. T’s functional ability due to his ongoing chemotherapy, we had our tough moments. But after spending an hour and a half together every day, we had developed a solid relationship.

By Rachel Seltman

The easy part of the answer is that accepting palliative care does not mean giving up hope for a cure. Palliative care addresses the symptoms of a disease. It does not address the underlying cause of the disease, but many people receive treatment for symptoms and treatment for the disease at the same time. Someone undergoing chemotherapy to try to cure their cancer may also receive palliative care such as medication to treat pain associated with the cancer.

Whether choosing hospice means giving up hope for a cure is a slightly more complicated answer. Hospice usually is restricted to patients expected to live six months or less (sometimes 12 months or less). So going to hospice means accepting that you will likely die within the year. However, some hospice programs (and insurance companies) allow a patient to continue to receive curative treatment while they are receiving hospice care.

All of the above is important to know, but it isn’t enough to answer the original question. The above all assumes that the only “hope” is for a cure. The first time I questioned that assumption was watching the Closure 101 module, “A Primer on Palliative Care.” As the narrator mentioned “hope of a peaceful dying process,” I realized how limited my understanding of hope had been. A person in hospice may or may not still hope for a miracle cure, but that is not the only kind of hope.

Read more: Does accepting hospice or palliative care mean someone has given up hope?

By Jamie Fallon

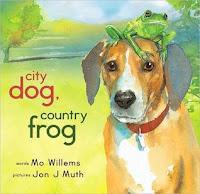

A few weeks ago I was perusing the shelves of a bookstore in search of gift for my nephew. Books are my favorite go-to gift for children, especially since I have a highly developed appreciation for quality children's literature from my experience as a teacher. I love books, and I love sharing them with others. When I go shopping for children's books, I enjoy meandering around the store and seeing what speaks to me as my eyes wander across the titles. There is an excitement that builds when expectations exceed that initial impression of the cover of a picture book as I flip through its glossy pages. And my most recent find drew me in like a magnet and left an impression on me in so many ways.

A few weeks ago I was perusing the shelves of a bookstore in search of gift for my nephew. Books are my favorite go-to gift for children, especially since I have a highly developed appreciation for quality children's literature from my experience as a teacher. I love books, and I love sharing them with others. When I go shopping for children's books, I enjoy meandering around the store and seeing what speaks to me as my eyes wander across the titles. There is an excitement that builds when expectations exceed that initial impression of the cover of a picture book as I flip through its glossy pages. And my most recent find drew me in like a magnet and left an impression on me in so many ways.

Read more: Children's Book Picks - City Dog, Country Frog by Mo Willems

By Jonathan Weinkle, MD

It’s been nearly forty years since Robert A. Heinlein wrote the novel Time Enough for Love, in which the immortal Lazarus Long comes to the realization that he is terminally bored. The two-thousand-year-old Long finds that he has exhausted the experiences that make life interesting and worthwhile, and wants to do the one thing that his unique genetics and repeated rejuvenation treatments render impossible—die.

We don’t live as long as Long, yet coming to the end of our much shorter life spans we also seem to find that the color has drained out of life in much the same way. Passion, fascination, and anticipation are replaced by a seemingly endless cycle directed solely at trying to extend life, without trying to fill it with anything.

By Jonathan Weinkle, MD

The supposed impossibility of predicting what will happen to a patient is one of the major reasons that doctors and nurses shy away from talking about prognosis with patients (see the "Prognosis" module in the "Closure 101" section of this website).

Perhaps part of the reason that patients and families do not access hospice services until near the very end of life (median hospice stay in the US is 18 days from enrollment to death) is because the getting Medicare to cover hospice care requires doctors to have a crystal ball after all. A physician must certify that a patient has a prognosis of 6 months or less if the illness were to run its normal course. Even using the "surprise test" (i.e. "Would you be surprised if this patient died in the next six months?"), physicians are very hesitant about making this prediction. Either they don't wish to do so in the presence of the family (lest they be seen as "giving up," "losing hope," or simply frightening the family), or they don't wish to put on paper a prediction that might, Heaven forbid, be wrong.

Read more: Have you ever heard a doctor say, “I don’t have a crystal ball”?

By Jonathan Weinkle, MD

But what if it isn't news?

What if the unpleasant facts, the inconvenient truth, has been there in the open for a very long time, but left unspoken? What if there is an elaborate effort being made to behave as if everything is OK, or will be made OK, when it is very clearly not?

What happens when you realize that it falls to you to speak the truth?

And what happens when the person who needs to hear the truth you have to tell them is someone you care about?