| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

|

|

7

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

12

|

13

|

|

14

|

15

|

16

|

17

|

18

|

19

|

20

|

|

21

|

22

|

23

|

24

|

25

|

26

|

27

|

|

28

|

29

|

30

|

31

|

Closure.org Blog

Search for hope has returned 9 results

New Palliative Care Certificate Program

Heaven forbid, if someone you loved was suffering from a stroke, you’d want them cared for somewhere where they would get the state-of-the-art care, right?

The Joint Commission (TJC) has certificate programs to recognize hospitals that meet or exceed the standards for stroke care; if your loved one is admitted to such a hospital, you get the reassurance of knowing they have TJC’s endorsement.

Now, what if your loved one was suffering from severe pain, anxiety, shortness of breath, or having a crisis of faith as a result of the treatment for one of the diseases above? Wouldn’t you also want state-of-the-art-care for those problems?

What Have You Got to Lose?

By Dr. Jonathan Weinkle

The longer I discuss end-of-life, the more stories I hear, the more nuanced my view becomes. Last month I facilitated a fascinating discussion that was meant to open an honest conversation about death and dying, to break down what I often call the Brighton Beach Memoirs approach to death – that is, whispering the word out of fear that, if we say it out loud it might happen to us.

The discussion ended with a personal story from one of the participants who was dying – her words, and her doctors – of a liver abscess two years prior, only to come back “escaped to tell thee” like one of the messengers coming to Job. What had saved her was a surgery that had one chance in a hundred of succeeding, and who knows what chance of leaving her dead on the operating table. Why was she undergoing the surgery? Her daughter insisted that, “If she’s going to die anyway, why don’t you operate? What have you got to lose?”

Sounds like anathema to the usual message of “caring before curing,” doesn’t it? Yet it is hard to argue with the outcome of this previously dying woman who walked into the room under her own power, sat attentively in a lecture and discussion for an hour, and chose this moment at the waning of our hour to articulately tell the story of how reports of her death had been greatly exaggerated.

(Read More >>)

Purple Sweatpants

By Stefanie Small

The Chevra Kadisha (Ritual Burial society) has been part of my life for as far back as I can recall. My parents are longtime members of this volunteer group of people who, as part of the Jewish tradition, prepare the deceased for burial. The members wash the person and dress them in shrouds and ready them for the final leg of this life’s journey. It is considered a “chesed shel emet,” a kindness of truth, done for no other reward than the knowledge that someone will do it for them when the time comes.

I became a member of the society about 10 years ago and have never looked back. It is a life altering experience to be part of the conclusion of a person’s existence in our world. The room where the work is done is quiet, almost reverent, as we know that we are the last to wash and dress this person. We are the final people to see the whole person as we place them in their caskets. And it is peaceful and hopeful and a reminder that life is precious.

(Read More >>)Does accepting hospice or palliative care mean someone has given up hope?

By Rachel Seltman

The easy part of the answer is that accepting palliative care does not mean giving up hope for a cure. Palliative care addresses the symptoms of a disease. It does not address the underlying cause of the disease, but many people receive treatment for symptoms and treatment for the disease at the same time. Someone undergoing chemotherapy to try to cure their cancer may also receive palliative care such as medication to treat pain associated with the cancer.

Whether choosing hospice means giving up hope for a cure is a slightly more complicated answer. Hospice usually is restricted to patients expected to live six months or less (sometimes 12 months or less). So going to hospice means accepting that you will likely die within the year. However, some hospice programs (and insurance companies) allow a patient to continue to receive curative treatment while they are receiving hospice care.

All of the above is important to know, but it isn’t enough to answer the original question. The above all assumes that the only “hope” is for a cure. The first time I questioned that assumption was watching the Closure 101 module, “A Primer on Palliative Care.” As the narrator mentioned “hope of a peaceful dying process,” I realized how limited my understanding of hope had been. A person in hospice may or may not still hope for a miracle cure, but that is not the only kind of hope.

(Read More >>)Dealing with Denial

By Toni Steres

My grandfather is dying. I tear up just typing that sentence. He was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in August of 2010 and without going into details, was given 6 months to a year back in December of the same year.

As a registered nurse, I know how important it is for patients to make end-of-life decisions before you actually need them. I have many stories of patients who planned ahead—and ones where patients did not. As you can imagine, those who did not left their families in turmoil—“What did he want to have happen? Do you know? Does anyone in the family know?”

I hoped that my grandfather, being a planner himself, would be willing to discuss this with me. But the denial stage of grief is a powerful thing. When I first brought up the thought that plans needed to be made—he cringed and changed the subject. Later, he told my father that it depressed him when I brought up the subject.

(Read More >>)End-of-Life Discussions: When is the right time?

Michelle Anderson

After she had experienced a few stays in the intensive care unit, I spoke with Sharon, a family member, about her preferences for care at the end-of-life. If she was ill again and things did not go as we'd hoped, what would she want? If the doctors aren't able to wean her off the ventilator, what should we do? She responded by saying "You made the right decision last time."

Several years passed by and fortunately Sharon was in good health. My husband and I recently saw Sharon at Thanksgiving along with our extended family, including Aunt Jean, who was feeling slightly under the weather with a cough. Thinking that it was nothing but a cold, my husband and I gave our ritual hugs and said goodbye. As we left, we smiled when we thought of her cheerful personality and the spunky glitter hat she was wearing, which fit her to a T.

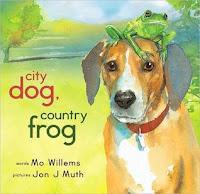

(Read More >>)Children's Book Picks - City Dog, Country Frog by Mo Willems

A few weeks ago I was perusing the shelves of a bookstore in search of gift for my nephew. Books are my favorite go-to gift for children, especially since I have a highly developed appreciation for quality children's literature from my experience as a teacher. I love books, and I love sharing them with others. When I go shopping for children's books, I enjoy meandering around the store and seeing what speaks to me as my eyes wander across the titles. There is an excitement that builds when expectations exceed that initial impression of the cover of a picture book as I flip through its glossy pages. And my most recent find drew me in like a magnet and left an impression on me in so many ways.

A few weeks ago I was perusing the shelves of a bookstore in search of gift for my nephew. Books are my favorite go-to gift for children, especially since I have a highly developed appreciation for quality children's literature from my experience as a teacher. I love books, and I love sharing them with others. When I go shopping for children's books, I enjoy meandering around the store and seeing what speaks to me as my eyes wander across the titles. There is an excitement that builds when expectations exceed that initial impression of the cover of a picture book as I flip through its glossy pages. And my most recent find drew me in like a magnet and left an impression on me in so many ways.

City Dog, Country Frog (2010, Hyperion Books for Children) by Mo Willems tells a playful and touching tale of friendship and life. One day, a dog befriends a frog waiting by himself in a field. The story unfolds sharing the games the unlikely pair plays as the seasons pass. The friendship evolves subtly over time. Then one winter, Dog is met by an empty rock and is left to cope with the loss of his friend, Frog. The story continues by demonstrating the processing and honoring of a loved one who has died, but it also reveals the cycle of moving forward and embracing new life experiences once again.

The sparing words and beautiful watercolor illustrations, by Jon J. Muth, tell a complex story in the simplest of terms. The book is relatable to both children and adults. I found myself tearing up as I read its pages in the bookstore. I knew I found something special. I gave pause in considering this book as a gift to my nephew because of its sad themes, but I also felt it sends a message of hope. City Dog, Country Frog seems like an appropriate vehicle to encourage healing as he has suffered the loss of a dear family member and beloved pet. Plus, he absolutely loves all animals.

Learn more about City Dog, Country Frog by listening directly from the author in this video. You may like to visit Mo Willem's official website to explore his other titles, as well. Many of these leave you in tears, but mostly because you are laughing so hard.

Have you ever heard a doctor say, “I don’t have a crystal ball”?

By Jonathan Weinkle, MD

The supposed impossibility of predicting what will happen to a patient is one of the major reasons that doctors and nurses shy away from talking about prognosis with patients (see the "Prognosis" module in the "Closure 101" section of this website).

Perhaps part of the reason that patients and families do not access hospice services until near the very end of life (median hospice stay in the US is 18 days from enrollment to death) is because the getting Medicare to cover hospice care requires doctors to have a crystal ball after all. A physician must certify that a patient has a prognosis of 6 months or less if the illness were to run its normal course. Even using the "surprise test" (i.e. "Would you be surprised if this patient died in the next six months?"), physicians are very hesitant about making this prediction. Either they don't wish to do so in the presence of the family (lest they be seen as "giving up," "losing hope," or simply frightening the family), or they don't wish to put on paper a prediction that might, Heaven forbid, be wrong.

Closure came into being with the lofty goal of becoming a "social movement" with a goal of changing expectations for end-of-life. The change we were seeking was that patients and families could comfortably expect that the care they received at end-of-life would be of the highest quality and consistent with the most evidence-based standards available.

In that vein, there now seems to be a movement afoot to rethink the arbitrary 6-month hospice requirement, in order to excuse doctors from doing something they admit they're lousy at (predicting the future) and get back to the core skills of their profession – relieving suffering and caring for patients in the way that best suits that patient. I have read one too many non-fiction accounts by physician-writers of "The patient who failed hospice." People don't "fail" hospice – but hospice occasionally fails them when it sets arbitrary requirements for who can use it and who can't. Hospice providers become, ironically, victims of their own success when someone survives their 180 days peaceful, comfortable, and still kicking, and the next kick is the one that kicks the patient off the services that have been providing them quality of life for half a year.

Time to review the evidence and revise the rules, I think.

No One Wants to be the Bearer of Bad News

But what if it isn't news?

What if the unpleasant facts, the inconvenient truth, has been there in the open for a very long time, but left unspoken? What if there is an elaborate effort being made to behave as if everything is OK, or will be made OK, when it is very clearly not?

What happens when you realize that it falls to you to speak the truth?

And what happens when the person who needs to hear the truth you have to tell them is someone you care about?

This is what happens when people die in sickness and in old age. And for those who find themselves in the position of needing to say the unspeakable, to point out that the sign over the door says "Cancer Center," or to call attention to the fact that the dinner tray has been sent back untouched every night for a week, here is what happens:

You don't wait a second longer. If you don't speak the truth, someone else will do it more clumsily and cruelly than you would have.

You don't delude yourself into thinking that you are doing anyone any favors. There will be sorrow. There will be tears. There may eventually be understanding and acceptance, but you are doing the dirty work. Expect to get dirty.

You don't swing your words like a sword or a club, cutting or bludgeoning people with them. Hold a hand, and press it, firmly but gently against the truth. "I am here and holding you tight, but you need to touch reality, run your fingers over the surface of sorrow, sense the thing that you have been denying all this time – and then I will hold you tight some more."

You don't expect an immediate reaction. Babies and toddlers fall, bump their heads, and often look around to see how others are reacting. If you are calm and compassionate, maybe there is no meltdown. Or perhaps the pain is so acute that they enter the silent scream, gathering strength to wail with all their might. You must be ready for either.

You don't walk away. You are at the bedside, the graveside, the fireside when you are needed, to continue holding that hand. You can be remembered as the one who shattered hope, or you can be remembered as the one who carried the burden as the survivors woke from an impossible dream and began a painful journey toward acceptance and reintegration.